#heart berries

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Excerpt From: Terese Marie Mailhot. “Heart Berries.”

#topic: heartbreak#terese marie mailhot#heart berries#quote#quote blog#literature blog#literature#literary quotes#academia#light academia#poetry#poem#poetry blog#follow for follow#follow 4 follow#indigenous#indigenous peoples#first nations#indigenous authors#heartbreak#heartbreak quotes#my collection#dark academia

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

"How could misfortune follow me so well, and why did I choose it every time?"

-Terese Marie Mailhot, Heart Berries

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

It almost feels like a betrayal to have good thoughts. Sometimes I know a part of me is still a ghost, walking next to my mother…

Terese Marie Mailhot, Heart Berries

#terese marie mailhot#heart berries#prose#memoir#indigenous literature#quote#literature#lit#healing#recovery#moving on#trauma#mother daughter relationship

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

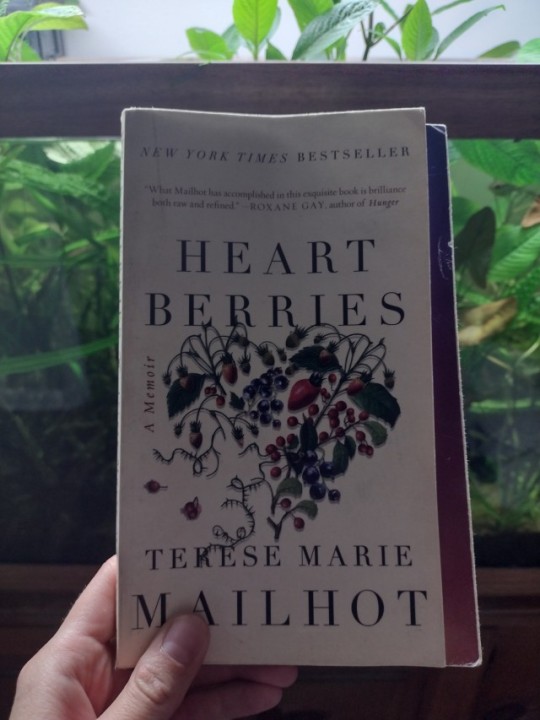

Book review: Heart Berries by Terese Marie Mailhot

This is a short but very impactful memoir. The author is a Salish woman who wrote this book as a series of essays when she was hospitalized. The writing style is quite unique. A lot of it is in second person, and other parts are almost stream-of-consciousness. Additionally, some parts are very poetic and/or ambiguous, and others are very direct/blunt. The author talked about her feelings of anger from years of parental neglect, a teenaged marriage that was violent, losing custody of one of her sons, childhood sexual abuse, another relationship with emotional neglect/cheating/abandonment, poverty, institutionalized racism, and being diagnosed with post-traumatic stress and bi-polar II disorder. What I liked about this book was that a lot of it was basically a giant call-out to many people either directly responsible for her suffering, or were too dense and judgmental to understand why she had the problems she had.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Thunder is contrary. Thunder can intuit, and her action is the music caused by lightning. She comes because we ask, and that's why falling apart is holy."

— Terese Marie Mailhot, “Heart Berries”

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

if i think about the hunger games in peeta's perspective i WILL start sobbing

#imagine you're a boy who's going to die. you're in love with the girl you've been watching from afar. you know your fate.#you just want to help her‚ but then there's the announcement and she's here in front of you‚ kissing you‚ risking her life for you and you#think‚ i could live and i could love. you think she loves you when she hands you the berries‚ when she puts them in her mouth.#then you both survive and you go back home and nothing is real anymore. you have nothing. no family. no friends. no love. just an empty#house. a drunk for a neighbor. the love of your life walking into somebody else's arms. you think‚ i survived the games. i could survive#this. and you also think‚ i should've bit down on those berries‚ should've felt the juice burst before i died.#and then the third quarter quell announcement rings in your ears and you think‚ she will live and i will die as i should have in the first#place. the girl you love kisses you on the beach and somewhere you heart stirs and your mind revolts and you savor every touch she has ever#given to you‚ in front of the cameras and off. because you are a tribute and you are always being watched and snow's presence looms and#you think‚ i know she cares. but you get taken. you get drugged. you get tortured‚ your mind altered. the girl is a mutt‚ a murderer. she's#everything you despise‚ your mind stirs. your heart revolts. you gain more awareness but cannot distinguish reality from fiction and you#have never known katniss' love. the war ends. you heal. you come home. you plant primrose for her. years down the line‚ you grow in love#more than you thought possible. but some days‚ you cannot tell fiction from reality so you ask the love of your life‚ you love me.#real or not real? and she says‚ real‚ and kisses you.#and you sigh and kiss her back and revel in this. a home. a life. a love.#lit#the hunger games#everlark#otp: real or not real?#katniss everdeen#peeta mellark#text#tais toi lys#thgpost#*

20K notes

·

View notes

Text

It's a whole set now btw.

#There's still like a couple details on the skirt I need to finish#the fake buttons are going to be knitted flowers because I cant find anything I like#also adding the same flowers to a couple of the berry clusters#also the skirt will have heart cable pockets#knitblr#knitters of tumblr#knitting#knitwear#cottage#cute#fashion#alternative fashion#japanese fashion#strawberry#cable knit#cottagecore#cottage aesthetic#my post

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Easy Heart Shaped Pastries

#easy#hearts#pastry#food#valentines day#baking#recipe#berries#strawberry#fruit#whipped cream#puff pastry#nutella#chocolate#hazelnut#nut butter#nuts#sarahsdayoff

866 notes

·

View notes

Text

#valentines day#valentine#heart#heartcore#love#lovecore#food#cooking#baking#sweet#dessert#delicious#berry#berries#strawberry#strawberries#pie#Aesthetic

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

I really need the official accounts to release all the Tulsa footage, like now. On YouTube.

Enjoy our gang in Tulsa!

#outsiders broadway#outsiders musical#brody grant#sky Lakota-lynch#joshua boone#kevin william paul#brent comer#jason schmidt#daryl tofa#Emma Pittman#dan berry#outsiders#spreading some joy and good vibes#since some people make it their life’s mission to rip that from us#and to them I say in my best southern voice#bless your heart

145 notes

·

View notes

Text

Text ID: “Falling in love felt fluid. It snowed when we fell in love. Everything reminded me of warm milk. Everything seemed less real. I thought my cup was overflowing. I found myself caressing my own face”

Excerpt From: Terese Marie Mailhot. “Heart Berries.”

#literature blog#poetry#literature#poetry blog#academia#light academia#feminist theory#heart berries#terese marie mailhot#indigenous authors#indigenous#indigenous peoples#first nations#native american#female authors#female poets#poem#literature quotes#quote#literary quote#falling in love#my collection#topic: falling in love#falling in love quote#falling in love quotes#dark academia#romantic academia#dark acadamia aesthetic

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Interview with Terese Marie Mailhot about her book Heart Berries conducted by Joan Naviyuk Kane

I couldn't find a text version of this interview so I transcribed it from the audiobook. Apologies for any errors.

Question. What has been your experience as a writer and reader within the general field of Native memoir? Most specifically, can you delineate your choices to write intimately, honestly, lyrically, compellingly?

Answer. Joy Harjo and Elissa Washuta's memoirs were in my periphery as I was considering writing one myself and I considered the memoirs of Leslie Marmon Silko and N. Scott Momaday and Linda Hogan when I thought about my aesthetic. When I look at these books, the distinctions are clear. The voices are present and impactful.

Different, obviously. And then I saw the literary criticism or lack of and these books were being mishandled to essentialize Indigenous people's art. Not so much Elissa's book and people could stand to write about it more because her work is fascinating and cerebral and new. But the genre marketing of Native memoir into this thing where readers come away believing Native Americans are connected to the earth and read into an artist's spirituality to make generalizations about our natures as Indigenous people.

The romantic language they quoted or poetic language they liked, it seemed misused to form bad opinions about good work. It might have been two in the morning when I emailed you one night. I was in Vermont lying on this dingy residency bed and I had [Harjo’s book] Crazy Brave open on my chest. I thought, I need to tell people that my story was maltreated and I need to make an assertion that I am nobody's relic. I won't be an Indian relic for any readership. So I decided this book would stand apart from some of the identified themes within our genre.

full interview under the cut

Question. Native literary writers are often compelled to or must take on a great deal of social context. How did you contend with that in this book?

Answer. I hope that people can contextualize the state of our world in my work. The writers before me seem to do the work of looking at being Indigenous so we could look through it. In many ways the experimental form, language, everything, I feel freer to do that because so much was done before.

Question. Can you talk about how the book began as fiction? How did you make the decision not to hide behind characters?

Answer. The original drafts of the chapters “Heart Berries” and “Indian Sick” were written and published as fiction. It was my intention to write with a polemic voice and have a First Nations woman character be overtly sexual, ruined and ruining people's lives, respectively. It was an audacious feeling to write a Native woman as gratuitous even if it was ruining her. It empowered me. And then I was in Starbucks holding a cup of coffee and I had the memory of my father in the shower with me. And I believe I was five or six at the time.

It was shaky and I had to write that down. And it was my final semester studying fiction at the Institute of American Indian Arts. Instead of using that semester to finish my book of fiction, I started writing essay. I realized that I had been using the guise of fiction to show myself the truth. And the process of turning fiction into nonfiction was essentially stripping away everything that didn't actually happen to me and filling those holes left behind with memory. It made sense that the fiction and then what came after. It's so different, but it makes sense bound together and retold as truth because there really was a before and after that memory.

Question. Do you think Heart Berries approaches the politicization of grief? What power dynamics move to the fore in writing this book? I mean in terms of narratives that the book brings together.

Answer. I didn't think about the politicization of grief, but the worst part of me imagined I could be redeemed.

Question. Can you talk at the craft level about what it means to work with the risk of self-disclosure? Can you talk about what it means at the level of personal relationships, alliances, political relationships? When you were writing the book and now that it is moving into production, what are your observations about the extent to which your writing is politicized, removed from context, or made to be in the control somehow of, if not the writer, one's readers? What are your perspectives on the different relationships a Native woman has to her audience of readers and the relationships she might have with the individuals that comprise her communities?

Answer. I moved with the surety that the work could not be as contrived as I normally present myself. Disclosure, personally, cannot work if I'm thinking rhetorically about appeal or thinking about appealing to someone I love. If I am gluttonous, exploitative, or punched a man, or tried to stab someone or failed my children, then I wanted to write it without rhetorically positioning myself as just. Crafting truth to be as bare as it feels was important.

Memoir, for me, functions as something vulnerable in a sea of posturing. The danger politically or artistically is that people won't give me my craft. Because I'm an Indian woman, someone might call my work raw and disregard the craft of making something appear raw. Raw would be fighting for myself, defending myself, telling people how hard it is to write about molestation and repeatedly saying I was a child. Because I wanted to do that, constantly give refrain and remind myself it was not my fault, but I didn't want to engage in sentimentality, or the wrong type of sentimentality. I crafted the voice and, while it's earnest, it takes work to be earnest and cut my shit.

I wanted to give my life art because nobody had given my experience the framework it deserved, as complex, more than raw, or brutal, or familiar, or a stereotype. I don't know.

Question. Shame and forgiveness have very different functions and histories in my tribal communities and in the space that a Native woman is permitted to inhabit in dominant culture. So here's a question. What, if anything, do you anticipate about these perhaps competing responses from readers? And please tell me you were not preoccupied to the extent of self-censorship with the notion of competing responses while you wrote the book, or rather, please discuss.

Answer. I knew nothing I said would change the trajectory of my life. Not in any real way. The work would not make it easier for me to move bureaucratically as an Indian woman. It would not make people processing a Native girl’s casework any different, because I believe we all try to articulate our stories, our voices, to those people, and they do not see us differently. I don't feel burdened when I say that, but I feel chagrined. That's a big part of the book. Shame. Being chagrined by my transgressions and my family’s. And I didn't censor that exploration. I hate the word exploration. It feels funny to say it because those words don't do it justice. It feels colonized to say I explore or discover.

But what other word could I own? The terrain was there inside of me and I decided to meditate or examine it with brutal honesty because I knew if I wrote it, I could know it. I could know the depth of my pain if I wrote it, revised it, and it felt true or as true as words can be. I wrote explicitly in some ways to display shame. True shame is the ugliest thing, the most hurtfully honest thing I can say about myself or another person, and then I revised it to cut deeper. And then I cut the fat off it so that the truth felt expedient, but it wasn't for me. Maybe that was a type of censorship.

I didn't want readers to do the interior work I did to arrive at a specific point. The book is structured by pain. What I did with that shame arrives at something pure, I think, which is that my mother is a biblical character in my story. Her and her mother and her mother have become larger myths than I originally thought.

Question. You've said elsewhere, “Indigenous identity is fixed in grief.” Can you elaborate?

Answer. I don't feel liberated from the governing presence of tragedy. The way in which people frame our work, and the way our work exists or is canonized. We are not liberated from injustice. We are anchored to it. It feels inescapable and part of the zeitgeist of Indian in the 21st century, or every century since they came, which doesn't limit me, or us, but limits the way we are seen and spoken about. It's unfortunate, and real to me.

Question. I asked about why you wrote the book and you said, “One reason I wrote the book is there is so much criticism about the sentimentality of writing about trauma. Writing about it is irrefutably art, but also does the work of saying something. Women should be able to say this and say it however we want. There's so much pushback about how a child abuse narrative can't be art.” Can you say more?

Answer. I know the book isn't simply an abuse narrative, but then it is. I was abused and brilliant women are abused often and we write about it. People seem so resistant to let women write about these experiences and they sometimes resent when the narrative sounds familiar. It's almost funny because yeah, there's nothing new about what they do to us. We can write about it in new ways, but what value are we placing on newness? Familiarity is boring, but these fucking people, they keep hurting us in the same ways. It's putting the onus on us to tell it differently. Spare people melodrama, explicative language, image, and make it new.

I think, well, fuck that. I'll say how it happened to me and by doing that, maybe it became new. I took the voice out of my head that said writing about abuse is too much, that people will think it's sentimental or pulling at someone's pathos, unwilling to be art. By resisting the pushback, I was able to write more fully and at times less artfully about what happened. I remember my first creative writing professor in nonfiction asked his class not to write about abortions or car wrecks. I thought, you're going to know about my abortion in detail. If only there had been a car crash that same day. I don't think there's anything wrong with exploring familiar themes in the human experience. When the individual gets up and tells her story, there's going to be a detail so real and vivid it places you there and you identify. I believe in the author's right to tell any story and the closer it comes to a singular truth, the more art they render in the telling.

Question. Can you speak to the competing impulses of memoir being therapeutic at the expense of being imaginative or provocative, hurtful, critical?

Answer. Cathartic or therapeutic. Those words are sometimes used to relate a feeling, like a sigh of relief or release. But therapy is fucking hard. My therapist didn't pity me, not the good ones. They made me strip myself of pandering, manipulation, presentation. They wanted the truth more desperately than I did. And then they wanted me to speak it. Live it every moment.

I feel like writing is that way. Writing can be hard therapy. You write and then you read it, revise your work to be cleaner, sharper, better, and then when you have the best version of yourself, not rhetorically, but you've come close to playing the music you hear in your head, you give it time and reread it. You go back to work. It seems endless. Nothing is ever communicated fully. The way being healed is never real unless every moment of every day you remind yourself of your progress and remind yourself not to go back or hurt someone or do the wrong thing. It's not healing unless you keep moving. You're never done. The work of never done, therapy and writing.

Question. Within the work, you most explicitly name one influence. “Her name was Adrienne, like a poet I loved. A woman of exclusion who loved women enough to give her work solely to them. Adrienne was part of a continuum working against erasure.”

Her friendship and support of Jean Valentine, one of my mentors and teachers, brings up another literary lineage. How does this assert, in some ways, that a woman's story is a story for every woman? And what, if any particular aspect of her work is this referencing?

Answer. Adrienne Rich, Diving into the Wreck. This book is sometimes for her. Everything she's done for me.

Question. Can you talk about the necessary contrivances Native writers often have to employ to make their work accessible, not just to dominant culture, but also to other Native writers? Overdetermination, surfaces, any evasions, elusiveness?

Answer. People want a Native identity crisis. The most digestible thing we can do is to note what it's like being an Indian somewhere Indians aren't supposed to be. Anywhere in North America, really. We want to see that, too. To some degree. I feel some type of affinity for the Indian in the sculpture [by James Earle Fraser,] End of the Trail. I want to be that Indian.

But no. The reckoning or feudal endeavor of being Indian. There's profundity there. But ultimately, it's false and contrived. Put upon us because they want us to stay relics. And romance is beautiful. Relics are beautiful. I feel pulled in and I resist.

Question. There are several images in the book that do the work of expressing without formulating, such as a spinning wheel, a white porcelain tooth, a snarling mouth, and lighting haunted me. How does this series of images foreshadow the consciousness at work in the book?

Answer. These images felt jarring to write as one sentence. I was torn, but there are all the indicators that my power was in something destabilizing. That was electric and white. That would not let me be. That was pressing and could not be contained. It was a matter of time. I was so terrified of myself and the things I saw. And my mother was right there the whole time, telling me to let it be. Let it exist within me and stir. And maybe women experience this. Thinking refrain is admirable, when cut loose is what it needs to be.

Question. As Native writers, and particularly as Native women writers, our lives are literally and mythically born through catastrophe, innocence, and destruction. You ask early in the book, “How could misfortune follow me so well and why did I choose it every time?” How does this inform your content and context?

Answer. When I read this, I feel the compulsion to literally look back because misfortune is always here behind me.

Question. You say too, “In white culture, forgiveness is synonymous with letting go. In my culture, I believe we carry pain until we can reconcile with it through ceremony. Pain is not framed like a problem with a solution. I don't even know that white people see transcendence the way we do. I'm not sure that their dichotomies apply to me.” How do you write pain into phenomenological circumstance?

Answer. I think pain is presented as good for us, that we can even identify it. Before, it was a secret. In my mother's time, it was a secret burden, and women were admired for their ability to ignore, to be silent, to be selfless. They were the backbone of every significant movement in our history because they were not cast to the front. Now we can speak it. And that's true healing, not a problem. To admit there is some constant pain.

Question. In the chapter, “Thunder Being Honey Bear,” you write, “I avoid the mysticism of my culture. My people know there is a true mechanism that runs through us. Stars were people in our continuum. Mountains were stories before they were mountains. Things were created by story. The words were conjurers, and ideas were our mothers.” In conversation about this work, you said, “Everyone in our lives exists right now.” I'm interested in the way the words true mechanism enmeshed themselves with the metaphor of language as an extension of the fabric of the lived world. How do you work within or without these figurative suggestions?

Answer. This ties into the images I saw when I was a child, the spinning wheel. Beholding myself was facing the wheel, which literally appeared to me. It didn't feel mystical. It felt like an image that came to me, an abstract part of my identity's collage or composition.

And I believe that is also how I regard my culture. We spoke the world into being. Mountains were stories before they were mountains, especially where I'm from, especially when my name translates to little mountain woman. Having the name introduced the question of if I or the mountain came first. Which do I regard as origin or speaker? And I think those questions definitively answer the nature of the people I grew up with.

Question. Your book presents so many dimensions of motherhood, both from your perspective as a daughter and as a mother. “Even mom's cynicism was subversive. She often said nothing would work out.” You present pessimism differently than cynicism, as irony that has to be lived rather than merely understood, right? How does this reconcile with your mother's operating principles?

Answer. She was hilarious in that she dedicated herself to the betterment of Native people but never believed in it. She discouraged herself from believing things could be better while working toward it. I guess she didn't want to jinx healing. Being cynical when people were so desperate for altruistic, new age, good time healing, it was a funny thing to watch that still brings me joy.

Question. The way in which you interrogate the failures of conversation is grounded in imperative and observation. Like when you write, Mom, I won't speak to you the way we spoke before. We tried to be explicit with each other. Some knowledge can only be a song or a symbol. Language fails you and me. Some things are too large.” What can you say about the function of ritual language by contrast?

Answer. My mother needed the poetry of biblical work. She needed an epic when I tried so hard to show her the truth in explicit language. Instead of saying, Larry touched me, she needed to hear about the death in his presence, that he was a ghost. She would have heard that and known the depth of the pain her boyfriend caused me. And she wouldn't have been defensive about it. Somehow saying things explicitly was never enough.

We never found language. Had I told her that she was my Jesus and that now I need her to wash me from sin, that's something my mother would understand, poetry, because reality was not real to her. I had always thought she was evasive, but I believe now that the more I tried to create finite parameters, realities, truths, messages, the more I tried to do that, the more she misunderstood. We both wanted something abstract from each other, and those desires aren't fulfilled by plain language. Plain language does not serve love.

Question. Later, you say, “I preferred abandoned over forsaken, and estranged to abandoned. I loved with abandon. It's something I still take with me. Estranged is a word with a focus on absence. I can't afford to think of lack. I'd rather be liberated by it.” What are the ways in which you construct absence or departure as possibility?

Answer. In some ways, I acted with reckless abandon because I had been abandoned. There was no father to work against or for. There was nothing, and it didn't always feel like absence, but a white room to paint.

Question. In another moment you write, “In my kitchen, I turn the lights off again, like I used to. It allows me to feel as nothing as the dark. I know where everything is, like I did before. I become scared because it is this behavior that causes me to commit myself. I still take a knife and I press it against the fat of my palm—in the dark, hoping that I have the bravery to puncture myself, so that the next day I can be more fearless.” Is this less about a connection to an individual body and more about a mode of survival?

Answer. This is hard to admit, but I thought I could gradually build my tolerance to physical pain and die, and that never happened. I just couldn't move forward to my destruction, and I couldn't appreciate death, even though I tried. Death becoming less interesting artistically, physically, heart-wise, it was the best thing I came away with.

Question. What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you think the current questions are?

Answer. I wanted to articulate the truth, but was unsure if the truth could be singular. I had existed in a double consciousness to the point where I wondered if I were an object or paralyzed in fear, and the book is me moving forward and putting myself at the apex of my own story. It's not immediate, but gradual, because it was happening as I was writing it, or as I was trying to articulate the truth of what exactly happened. In the first chapters, I am asking if my father hurt me, then how, and then finally, I can behold myself. And that could be why it's roving temporally, or not really concerned with a linear structure, but with the story as it should be presented, rhetorically and truthfully. Questions exist in the last pages of the book. Is the uncovered truth and the knowledge of it wholly enough for me to move away from? Is admitting the nature of my father or my mother's transgressions and my own, or realizing I've entered my own renaissance enough to let the worst parts of my father, mother, and myself rest?

So where are we now? With Terese Mailhot’s Heart Berries we move well beyond the yesteryear's satisfactions of mere representation and oblique lyricism. The reader now anticipates that the forefront of contemporary indigenous literature will imbue terror with angst, of course, and that we are no longer tasked with the hauntings of various types of loss. That silence, too, is a construction. That we are no longer complicit in presenting Native experience as historical content rather than literary apotheosis.

I mean that silence is not representative of loss. I mean to call attention to the fact that, yes, through craft, we assemble what remains of ourselves through language. We imagine, create, tell, reprise, contradict, refuse, estrange, assimilate, and determine our language. What we do becomes part of our existing story. Even though at times our detractors, all of them, seem to argue that through language, we seem to exist in opposition to the very notion of story.

So, where are we? Who is telling whose story? Who is preventing misreading?

No one. Violence happens through our bodies. Isn't that how colonialism used to work? Their adversaries were simple. Our families, our genealogies, marriages, children, our sexual and domestic violence, and ourselves, our suicides, our recuperations, were simultaneously reduced and amplified as social facts rather than private matters. Our literature was not ours, it was theirs.

So, where are we? Where we have always been. Where are you?

0 notes

Text

I could not fathom being a good person when I came from such misery.

Terese Marie Mailhot, Heart Berries

#terese marie mailhot#heart berries#prose#memoir#indigenous literature#quote#literature#lit#trauma#healing#recovery#self esteem

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Belsnickel doodles!!

#first boggarts and now belsnickels have stolen my heart-#also my sudden obsession with mask wearing fools and then i get THIS#LIKE???#THE MASK WEAKNESS#THIS SMILING FOOL#GIMME SOME BERRIES PLEASE#home safety hotline#hsh#hsh seasonal worker#home safety hotline seasonal worker#hsh dlc#spoilers#hsh spoilers#home safety hotline spoilers#belsnickel#hsh belsnickel#my art#fan art#doodles

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

G2 My Little Pony comic #1 (1999), "Light Heart's Bad-Joke Day!"

#g2#mlp#my little pony#Light Heart#Petal Blossom#Sun Sparkle#Sundance#Ivy#Sweetberry#Sky Skimmer#Bright Berry#comics#scans

68 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Wonderful Swedish Christmas Decorating and Traditions for Today - Town & Country Living

70 notes

·

View notes